Reflections on the Plight of Women’s Rights in China through the Lens of the Iranian Feminist Movement

By WRIC Jing Zhang 12-04-2025

Note: This article is based on a speech delivered by Jing Zhang at the China Action X-Space discussion regarding the Iranian opposition movement.

Summary Abstract: Human rights activist Zhang Jing offers a thought-provoking comparison of the women’s rights movements in Iran and China. By analyzing the “Women, Life, Freedom” movements in both countries and the systemic oppression under their respective regimes, Zhang Jing points out that despite the different forms of resistance, the struggle for women’s liberation is inextricably linked to the overthrow of bullying in a patriarchal society and dictatorial rule.

Before 1979, particularly during the Pahlavi dynasty, Iran’s women’s rights movement secured significant progress. Women gained the right to education, the right to vote, and legal protections within the family, including fairer laws regarding divorce and child custody.

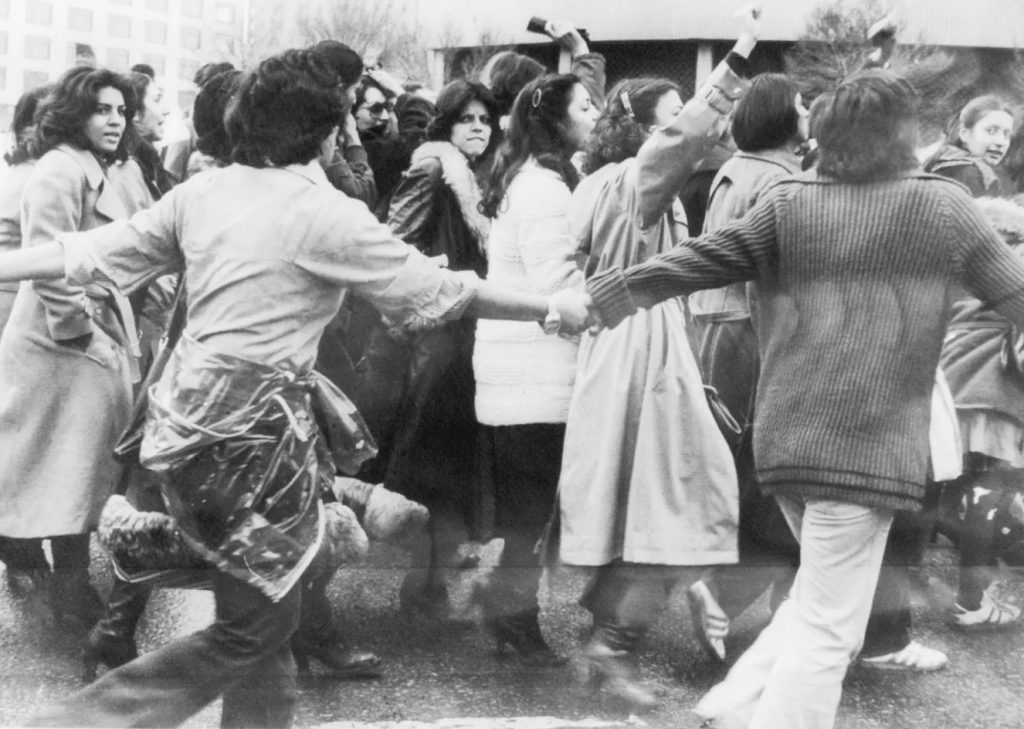

However, the landscape shifted dramatically with the 1979 Islamic Revolution and the rise of Ayatollah Khomeini. The 1967 Family Protection Law was abolished, and new mandates—such as the compulsory hijab and strict public dress codes—were introduced. Consequently, women’s rights were curtailed, and their social status plummeted.

Women protestors, surrounded by men as a form of protection, march against the veil in Tehran, on March 10, 1979. Bettmann Archive Getty Images.

In 2006, various Iranian women’s groups across the political spectrum launched the “One Million Signatures” campaign, demanding an end to discriminatory laws. Under Iranian penal law, appearing in public without an “Islamic headscarf” is a criminal offense, punishable by fines or imprisonment.

From Silence to Resistance: “Woman, Life, Freedom”

Despite decades of activism, it wasn’t until around 2014 that feminists found a unifying focal point: the movement against the mandatory hijab. In December 2017, the issue exploded into a political firestorm when Vida Movahed stood atop a utility box on Revolution Street, silently waving a white scarf. This bold act inspired the “Girls of Enghelab Street.”

Vida Movahed, pictured lifting her head scarf into the air on Tehran’s Enghelab Street, is credited with sparking a wave of protests in Iran against the compulsory wearing of the hijab.Photograph by Abaca Press / Sipa USA via AP

The movement culminated in September 2022 following the death of Mahsa Jina Amini in the custody of the “morality police.” The powerful images of women and girls taking to the streets chanting “Woman, Life, Freedom” garnered global solidarity. The Iranian authorities responded with brutal repression, resulting in the unlawful killing of over 500 protesters and the weaponization of sexual violence to silence dissent.

Amidst heightened international tensions and frequent exchanges of barbs between the US and Iran, the Iranian regime has found a “legitimate” pretext for even harsher repression of the women’s liberation movement. As 2025 draws to a close, the Iranian women’s rights movement shows no signs of significant progress. according to the UN, the repression of women in Iran has intensified in recent years, despite the mass protests.

According to the UN, the repression of women in Iran has intensified in recent years, despite the mass protests.

Photo by Iran Human Rights Monitor.

Comparing the Struggles: Iran vs. China

While women in both Iran and China face oppression under some of the world’s most authoritarian regimes, the situation in China presents unique challenges in terms of international representation and survival at the grassroots level. In other words, the Iranian government, using faith and law, openly persecutes, sexually assaults, and even executes feminists; while the Chinese government, unable to control its own laws, cleverly uses lies to deceive the international community, leveraging state power to distort, smear, and attack feminists, relentlessly depriving them of their right to speak and replacing their voice at different levels, both domestically and internationally, until the space for women’s rights is compressed to its absolute minimum.

We can look at it from three main aspects:

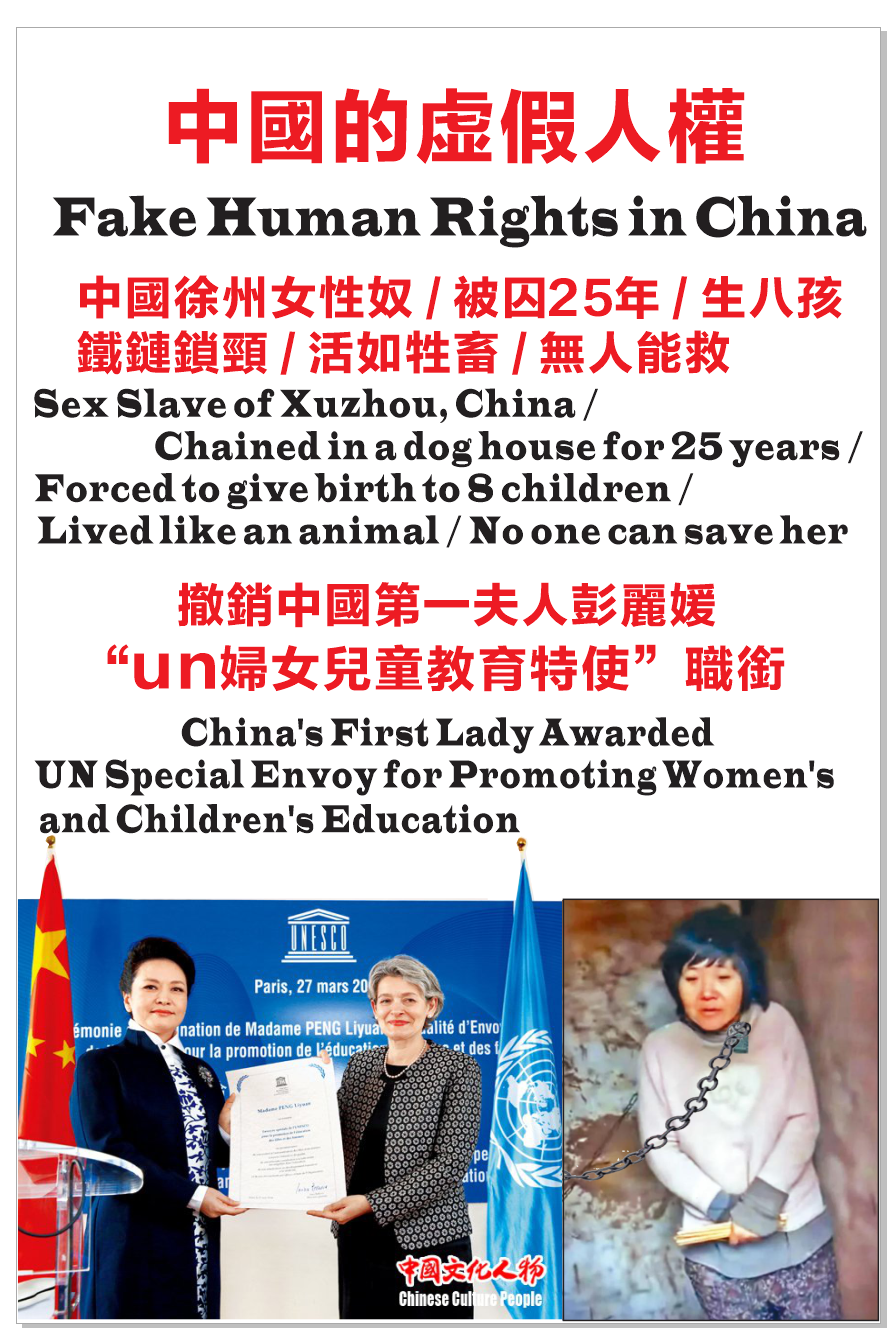

- The Monopoly of International Discourse

A prime example is Peng Liyuan, China’s First Lady, who serves as UNESCO’s Special Envoy for the Promotion of Education for Girls and Women. Despite her prominent position, she has consistently remained silent on the key figures and core demands of the grassroots women’s rights movement in China. In her public appearances, she has never addressed some of the most systemic cases that define today’s struggles—such as the Xuzhou “Chained woman” case, the Tangshan restaurant attack, and the alarming suicide rate among rural women in China (which has the highest suicide rate among its peer group in the world).

Peng Liyuan and state-led groups, including NGOs, have effectively hijacked women’s voices. They have crafted a glamorous facade of Chinese support for women’s rights to the world, masking the severe injustices faced by Chinese women in political, economic, and social spheres, and the real dangers faced by feminists.

Women’s Rights in China (WRIC) designed the poster.

WRIC designed the poster.

WRIC designed the poster.

WRIC designed the poster.

b. The Systematic Erasure of Grassroots Issues

Beyond institutionally suppressing and replacing grassroots feminist voices, the government also uses legal means to suppress feminist demands. In many #MeToo lawsuits, the vast majority of female plaintiffs are defeated, especially in cases supported by feminists.

Simultaneously, the government deploys a large and systematic online army funded by the government to distort, ridicule, and attack feminist ideas online, and to launch personal attacks and threats against feminist activists. Due to a complete lack of media and social support (only government-controlled media have a place in China), feminists are forced to “huddle together for warmth” in a small, isolated online circle. Landmark cases like the Xuzhou “chained woman” case were not only erased by the Great Firewall but also systematically suppressed by at least 200,000 officially supported women’s organizations from the central to local levels.

Furthermore, due to the government’s strict control over vocabulary and foreign news, even reporting on #MeToo and related movements is restricted. Moreover, it is no longer possible for grassroots feminist organizations to obtain funding from overseas feminist groups; any NGOs that received foreign funding were forced to disband or be forcibly banned years ago. Due to a long-standing lack of grassroots organization and planning, large-scale protests have been impossible, and women’s issues have been quietly excluded from the public sphere. Even symbolic performance art can lead to police harassment or arrest.

c. Differences in Direct Confrontation

Compared to the ongoing women’s street movements in Iran, social activism in China is relatively mild, often involving very small groups—rarely seen even in small groups of several people—and rarely receiving male support. In Iran, however, thousands of women take to the streets, undeterred by being beaten bloodied, often with large numbers of men stepping forward to share the batons and bullets of the police. In China, fierce resistance has devastating consequences, clearing the streets in minutes and bringing silence back.

Furthermore, in Iran, Naarges Mohammadi and her fellow inmates could burn their headscarves as a symbolic protest; but in Chinese prisons, any similar act would be life-threatening or result in life-threatening injuries. Moreover, due to the lack of organized grassroots forces in China, isolated activities often fail to generate a wider social response.

Conclusion: In Iran, the struggle is centered on visible symbols of oppression like the hijab. In China, the oppression is more systemic, rooted in the state’s total control over the narrative and the intentional atomization of activists. However, the fundamental truth remains: whether in Iran or China, as long as the current ruling regimes remain in power and until there is fundamental social change, true women’s rights will remain an impossibility.